Kang Woo-suk (강우석) has been called ‘the most powerful man in Korean cinema’. Why? Because, aside from his prolific and hugely successful directorial career reaching back to the 1980s, he has also produced and/or helped finance approximately 140 films in Korea. His films as a director include the ‘Public Enemy’ series of thrillers, ‘Two Cops’ 1 & 2, suspense-mystery ‘Moss’, and ‘Silmido’, an action film about a planned real-life invasion of North Korea by South Korean marines in the late 1960s that became the first film ever to top 10 million admissions in Korea. His latest feature about mixed martial arts fighters is called ‘Fists of Legend’. The film has already been shown as part of the London Korean Film Festival, but it will be screened at Oxford on Nov 17. As the LKFF comes to a close, we offer this parting interview with one of Korea’s most successful filmmakers of all-time.

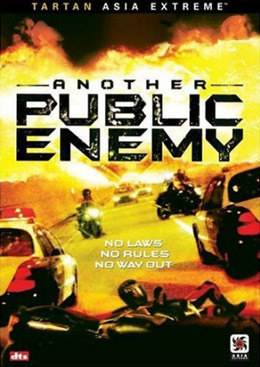

You are in London to show your most recent film, but also to be honored with a retrospective of your work. One of your most popular films is still ‘Public Enemy’ (공공의 적, first released in 2002). Did you expect that Public Enemy would be successful enough that you were able to direct two sequels to the film (in 2005 and 2008)?

It wasn’t really an issue whether the film would be successful or not. In the previous ten years I had made other films like Mister Mama and Two Cops – about five films which were hugely successful – so I was just playing around and didn’t really make any films for about three years; simply producing other films. It turned out that I wasn’t directing anything so I just quickly shot [Public Enemy] because I thought I needed to direct another film. If I had one hope from making that film it was whether as a director I could have a film that contained some entertainment within it. In terms of the two sequels that emerged from that, it was simply because the (Korean) audience really wanted to see those sequels.

You’ve worked with actor Sol Kyung-gu (설경구 of ‘Oasis’ fame, who was also in London to screen his newest film, ‘Hope’) on at least four or five films so far, including the massive hit ‘Silmido’. What is your working relationship like with Mr. Sol and do you have any plan to work with him again in the future?

Once Sol Kyung-gu starts working on a film, it’s not easy for directors to part with him, because he instills so much passion into the work and his attitude is extremely good, so in the span of five years I made four films with him and there was a mistaken belief going around at the time that Sol Kyung-gu only works with me. So we decided to have some time apart [since then]. However, for my next film – my 20th film – I’ll be working with him again.

The script for that film has not been completed yet so I don’t know how the story might change and it’s slightly awkward to tell you too much about it but it’s definitely a historical piece set in a time two or three hundred years ago and again it involves a detective in the story. It’s like a cop under an older guise.

How do you go about deciding whether you want to direct a project or simply produce it?

When I feel that it’s only me that can direct the film and I know I can do it, that’s when I will be directing it. If I don’t feel comfortable directing it but I feel strongly that this type of film needs to be made and needs to exist, that’s when I will be producing it.

What is your role as a producer like? How do you help each film you produce in general?

I help make the decision whether to make the film or not. When the directors actually shoot the film, I don’t usually interfere that much, but during the editing process I would be heavily involved. Because I’ve made so many films myself, it’s a case of using my experience to help them as much as possible.

Do you do auditioning for your films, or if you have an actor that you want, do you just contact them directly and ask them to be in your film?

In terms of the supporting cast and the minor roles below the main characters, the assistant director will be holding auditions to find candidates who would be suitable for the role and then I will contact them myself and make the final decision on that. In terms of the main characters, I will personally call them myself and say whatever you do, you have to make time from this period to this period. That’s how I decide about the actors.

Most of your films feature leading male actors in the primary roles. Is there any particular reason why you lean towards more masculine films (without leading actresses)?

Well, I don’t really like melodramas. I’m not really confident in portraying them; I’m not really interested in love stories either. Naturally, that has led me to make more masculine films. Even now, I’m more interested in making extreme and powerful films rather than love stories as you can see from my CV.

Your most recent film, ‘Fists of Legend’ (which is being screened at the 2013 London Korean Film Festival) was based on a webtoon (internet comic). Why do you think this is becoming a more popular trend these days?

Webtoons themselves are cinematic. They flow well on screen. They appear visually like a film because they are very flowing and it seems that they are very easy to make into a film because of the clarity behind them. Actually, one of my previous films called ‘Moss’ was based on a webtoon as well. The original webtoon was extremely popular and successful. However, the actual process of turning it into a film was extremely difficult. If you followed the exact webtoon, there’s really no reason to turn it into a film. So although it might seem appealing, it’s not an easy process at all. Fists of Legend was also very difficult in the process of making it. A lot of things that make sense in the webtoon don’t make sense after translating it onto the screen. But since ‘Moss’, the trend of making films from webtoons has really grown and I think it will continue in the future simply because there is a misconception that it looks really easy to turn them into films.

Your earlier films, such as Silmido and the Public Enemy series, up to your 2006 film ‘Hanbando’ (The Korean Peninsula) seemed to be more political in nature. Yet since that time you have steered clear of overtly political works. Is that perhaps due to some criticism you received around ‘Hanbando’ that it was too patriotic and anti-Japanese?

Yeah, that makes sense. It wasn’t really intended to be a very political film; it was shot from a fantasy-like stance, but the audiences watching it really took it to heart in terms of its nationalism etcetera and criticised it a lot. However, I really like the film and I enjoyed shooting the film so I don’t have any regrets from that. I think now I’m just at a stage of wanting to make more warm-hearted films, taking a break from the emotions that I had previously. However, my next film is extremely political and has a lot of satirical/social criticism so I think I have returned to [my earlier self].

Interview conducted at the Korean Cultural Centre in London by Tim Holm